By Michael Igoe

|

| The site of the University of Central Asia’s campus in Naryn, Kyrgyzstan. Photo by: Michael Igoe / Devex |

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is part two of a three-part Devex series that examines the Aga Khan’s plan to create a new model for higher education in Central Asia, where the opportunity to achieve academic excellence is usually found somewhere else. Read part one here.

Inside Ian Canlas’ science classroom, students are discussing their grades on a recent homework assignment.

One of them asks Canlas why he deducted points from an answer that seemed generally correct.

“Because you did not have a complete idea,” Canlas says.

The students are grouped around open tables, seated in lime green cushioned swivel chairs. A few of them have laptops open. Most are casually dressed in t-shirts and hoodies, except for one who wears a black suit. The tone is informal, familiar. They call Canlas by his first name, Ian, which rhymes with lion.

But for the jagged foothills of Kyrgyzstan’s Tien Shan mountains surging outside the window and the students’ non-native facility with English, this could be any freshman classroom at a well-equipped Western university. For many members of this class, however, their first months at the University of Central Asia have marked a dramatic transition from the rote memorization favored by their Soviet legacy high schools to a curriculum that demands they think critically, in English — and offer a “complete idea.”

While it is not unheard of for high-achieving — or well-connected — students from Central Asia’s rural regions to access top-notch universities, it usually requires their families send them to a capital city or abroad, and — if they’re not lucky enough to earn a scholarship — pay a steep tuition. With or without financial assistance, young people who don’t have access to a quality university nearby face a difficult choice: leave home and family to pursue it, or make the best of what’s around.

The Aga Khan Development Network — a multi-disciplinary development organization led by Islamic royal billionaire and spiritual leader Prince Karim Aga Khan IV — has sought to upend that birthplace lottery for a select group of students drawn from Central Asia’s mountain towns. With a massive investment in three rural communities — Naryn in Kyrgyzstan, Khorog in Tajikistan, and Tekeli in Kazakhstan — the Aga Khan is developing world-class startup research universities in parts of the world where public budgets have collapsed and educational institutions have struggled to keep pace with global change.

After a short introduction about the environmental impact of plastics, Canlas tells the students to grab their lab notebooks.

They crowd into the shining, dual elevators outside the seminar room, and their studious classroom demeanor briefly dissolves into bursts of giggling Russian. A few of them can’t help toying with the door open and door closed buttons on their way to the first floor laboratory.

The first minibus out of town

Valerie Lopes was afraid to visit the campus in Kyrgyzstan, not because she feared for her safety — though the 18-hour flight from Toronto to Bishkek, plus another four hours by car to Naryn was a daunting prospect — but because she worried students in the inaugural class at UCA would be up in arms over the intense preparatory curriculum she had spent the past 15 months designing.

“I was terrified,” said Lopes, director of teaching and learning at Seneca College in Toronto, who served as the academic lead for the team that created UCA’s preparatory year curriculum.

She gestured through the window of a borrowed office in the Naryn campus’ administrative wing to the two-lane highway that leads west into Kyrgyzstan’s sparsely populated heart. “I would have just picked up one of those minibuses and said — ‘how far are you going?’”

The Aga Khan’s vision for this startup international university is to deliver an educational experience on a par with the world’s elite institutions.

“I was educated at a research university, which is Harvard, and I believe that all countries need research universities. Those are the fora in which good research is done, in which young professionals are educated to perform,” the Aga Khan said in response to a question from Devex at the UCA Naryn inauguration in October.

But there is a key difference between the Aga Khan’s own experience and those of the students now attending UCA. The spiritual leader to 15 million Ismaili muslims and inheritor of a vast fortune enjoyed world class preparation for his world class university experience. He was born in Geneva, instructed by private tutors and then enrolled in Europe’s most expensive boarding school.

|

| Prince Karim Aga Khan IV talks to reporters at the UCA inauguration in Naryn, Kyrgyzstan. Photo by: Michael Igoe/Devex |

Students matriculating at UCA in Naryn — while they are among their countries’ best and brightest — have mostly not been groomed for elite Western universities. One member of UCA’s inaugural class is an Afghan refugee. Few of their parents can afford expensive private tuition.

The fact that a billionaire philanthropist is now opening such a university at the doorstep to Central Asia’s remote mountain towns presents a huge opportunity for students in the region, but it is an opportunity that comes with equal obstacles and questions.

Lopes’ job was to help answer one of the biggest questions — can you take high-achieving students from Central Asian high schools, put them through a year of intensive instruction, and bring them to a level of academic preparation equal to any first year, international scholarship student matriculating at Harvard, or the University of Toronto?

For students accustomed to post-Soviet pedagogy — which tends to look a lot like Soviet pedagogy — English-based instruction that emphasizes critical analysis is a big leap.

“I introduced brainstorming as a strategy,” Canlas said. One student responded, “We’re tired of brainstorming. Just let us know what comes up in the test and we’re going to memorize,” he recalled. “Their perspective is just different,” he said.

Every single class for the entire preparatory year has a lesson plan that’s been mapped out by the team Lopes directs from Seneca College, which won funding from Global Affairs Canada, the Canadian government’s foreign affairs agency, to undertake the work. Lopes estimates that every two-hour lesson that UCA’s teachers are currently delivering required about 12 hours for her team to create.

At first UCA’s instructors bristled at teaching a fully mapped curriculum, but they have since warmed to it, Lopes said.

The lessons are designed to be integrated and mutually supportive, so that, for example, students study color in science, at the same time they learn to calculate wavelengths in math, at the same time they learn about literary and non-fictional treatments of color in English.

“There’s this level of integration that most people have never had the opportunity to teach, even though we say that this is how we should be teaching,” Lopes said.

For Lopes this university in remote Kyrgyzstan, backed by the immense resources and uncompromising vision of an Islamic royal billionaire, has presented an opportunity most academic theorists could only dream of: A well-funded blank slate on which to implement educational programs that reflect the cutting edge of what is known about learning.

|

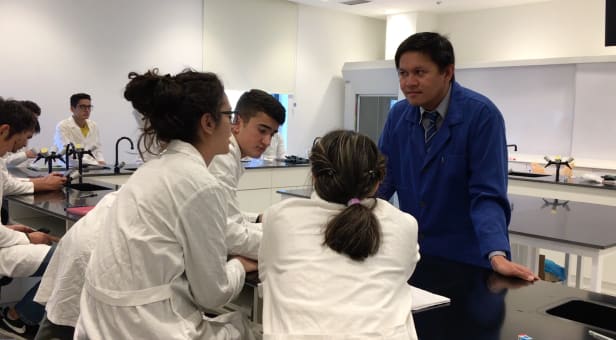

| Ian Canlas talks to students during a science lab. Photo by: Michael Igoe / Devex |

“It really is a unique — I don’t want to call it an experiment — but it is an experiment,” Lopes said, adding, “I can’t believe how long it took me to get here.”

To Lopes’ great relief, the students have embraced the curriculum.

“I guess a little bit of my excitement comes from what I found when I got here. I’m actually not nearly as worried as I was before,” she said.

An outrageous proposition

It has not been easy. The advantages of being a remote startup university with the freedom to pursue a vision have run up against some obstacles. UCA has struggled to attract teachers, for example.

Canlas, who said he was interviewed about 20 times before securing the job as UCA’s science teacher, has not seen his wife since May 2015.

That is in part due to his itinerant nature; Canlas previously taught at the Nazarbayev Intellectual School of Physics and Mathematics in Kazakhstan, and his wife is similarly busy supporting communities affected by Typhoon Haiyan in their native Philippines.

“Both of us are career centered,” he said.

But the distance and unknowns posed by UCA Naryn’s location in rural Kyrgyzstan have been enough to dissuade a large number of teacher applicants. More than half of the people who received initial job offers did not accept, according to Lopes.

The country of only 5 million people has largely disappointed expectations that it might emerge as Central Asia’s bastion of stable democracy. Post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan now commemorates two “revolutions” that occurred within five years of one another, and interethnic violence between Kyrgyz and Uzbek populations in the south threatened to devolve into widespread conflict in 2010.

“My sisters, and my mom, and my wife, they were so afraid about me coming to Kyrgyzstan,” Canlas said.

But the science teacher has grown accustomed to Naryn, a somewhat shabby town situated in a picturesque valley and on the banks of its rushing, namesake river.

“In the beginning I thought Naryn was really a tiny village, but as soon as I walk around and see that things are available, I don’t even think that it’s necessary for me to go to Bishkek,” he said.

The Aga Khan’s decision to place the three UCA branches in secondary towns away from Kyrgyzstan’s, Tajikistan’s and Kazakhstan’s capital cities was an integral part of his academic vision from the beginning. In the late 1990s when a commission that included AKDN leaders and Tajikistan’s minister of education formed to consider what this university might look like, the Aga Khan was clear.

“He said, ‘I’m not looking for another university in the center of Bishkek,” recalled Shamsh Kassim-Lakha, who served on the commission.

|

| Children wait at a bus stop in Naryn, Kyrgyzstan. Photo by: Michael Igoe / Devex |

The idea of locating top educational institutions in previously unremarkable places is not unheard of — it’s just unheard of in Central Asia.

“The whole idea that you can have quality institutions outside the capital cities is an absolute novelty over here. Everybody thinks if you’re not within the 10 square kilometers of the center of the capital it’s not worth it,” said Bohdan Krawchenko, UCA’s director general and dean of graduate studies.

Krawchenko noted that a majority of German universities exist far from Frankfurt and Berlin, while the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, with a population of less than 1 million people, is home to 10 public universities.

“Our’s sounds like an outrageous proposition in the Central Asian context, but it’s slowly hitting people that there is no reason on earth why providing a quality education cannot become an activity that is a generator of regional development in secondary towns,” he added.

A long journey

AKDN is also working to outfit its university with a curriculum and research focus that is relevant to the communities where it’s being taught. The university’s “product” is not just well-educated students, but knowledge and research that is applicable to Naryn, Khorog, Tekeli and other Central Asian mountain communities struggling to tackle complex challenges.

There is another Western-style university in Kyrgyzstan — the American University of Central Asia, located in Bishkek — that delivers an American curriculum and awards an American university degree. But that model is not what UCA’s leadership ever had in mind.

“We feel that if you’re going to train people to be the future leaders … in this part of the world, then they ought to be understanding what this part of the world means,” said Kassim-Lakha, who now chairs UCA’s board of trustees.

The approach speaks to a basic idea at work in AKDN’s relationship with the communities where it operates: that the organization’s role is not to import solutions, but to create and sustain institutions over a long period of time — and at an eyebrow-raising cost of well over $100 million, in UCA’s case — where people can develop their own expertise.

As Lopes pointed out, it would be much cheaper just to award the students UCA has drawn from Central Asia’s mountain towns scholarships to attend university in Europe or America than to undergo the institutional and academic construction that AKDN has committed to.

So why focus on something so expensive and complex in places that are struggling with basic public health and economic development?

“This is the perennial argument — go out and meet the Millennium [Development] Goals,” Krawchenko said, referring to the set of basic development goals agreed to by nearly all countries.

“The millennium goals are not that difficult to meet. The problem is, what do you do then?” he said.

Central Asia’s development challenges are analytically complex, Krawchenko said. How do you reform an education sector when your per student budget is less than $50? How do you think about economic growth when your GDP per capita is $1,900? What should be Kyrgyzstan’s political and economic relationship with China, its eastern neighbor and the world’s second largest economy?

“What has happened in these places is that thinking about these societies — policy reflection — has been outsourced. And that is a disaster. You don’t outsource reflection on the future of your country to consultants from the West,” Krawchenko said.

It is a long view of what it means to do development — but it is a process that countries that have moved successfully from dependence to independence have undergone.

“There’s no shortcut to getting out of the development problem, and it requires interventions at the bottom, obviously. What has been a problem, is actually interventions at the top,” Krawchenko said. “That’s our journey, and it’s a very long one.”

No comments:

Post a Comment